Why are golf balls dimpled?

Aerodynamics in Golf

Golf balls are instantly recognisable by their dimpled surface, but why are they designed to look like this?

Introduction

In golf, success is often dependent on how far you can hit the ball, with players with long drives being able to reach the green in fewer shots. This is where the dimples on a golf ball find their use. These dimples actually help the ball fly farther once hit, than if its surface was smooth. This was first discovered in the mid-1800s, and research ever since has caused the evolution of the golf ball to the design we are so familiar with today.

Adding these dimples does seem counter-intuitive at first; surely these dimples should increase the drag the ball experiences as it travels through the air? Shouldn’t this slow the ball down quicker and cause it to hit the ground earlier?

To understand exactly why the ball travels further we need to take a closer look at the underlying physics. Let’s first familiarise ourselves with the basics of projectile motion. If you feel like you’re confident enough with this level of basic mechanics, click here to skip to the more advanced section.

Throughout this page, we will look at how different effects affect the flight of a golf ball. If you are interested to know more about our modelling of the shot, you can download our Python script and try it out yourself.

Just click on the link below to go to our GitHub page and download the files!

If you aren't sure what is going on in the code, click the button below to view a page where we explain further.

Projectile Motion

First let’s imagine we are on the Moon, a place with very little atmosphere, and thus a place where we can assume there is no drag to affect the ball’s flight.

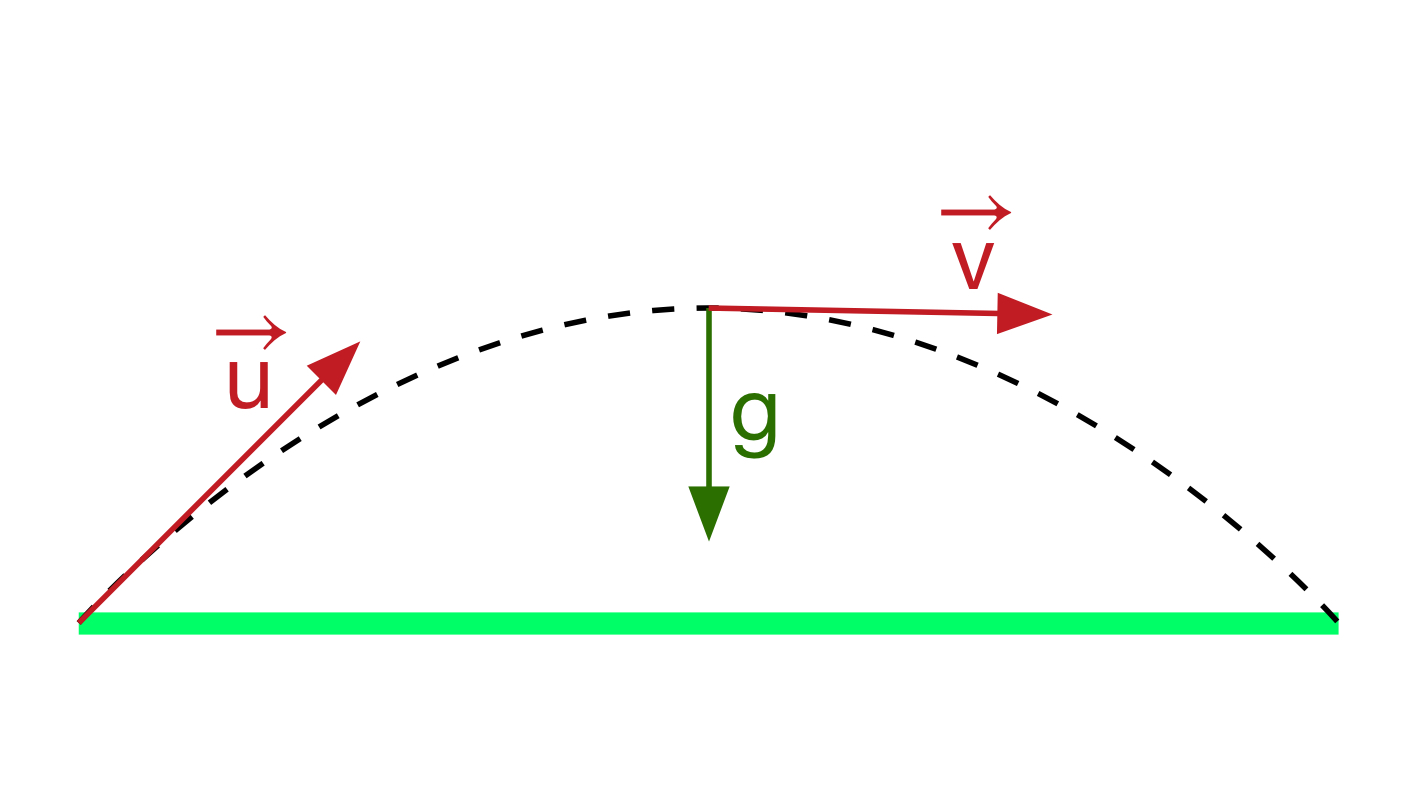

With no drag, we know that the only factors which affect the balls path through the air will be its initial speed, the angle at which it is launched into the air, and the force of gravity pulling it back towards the ground. In this case, the path will be a perfect parabola, as shown in the diagram below.

If we took the case of an average golfer, hitting the ball at 60m/s and an angle of 15 degrees, we can use this model to calculate that the ball will travel just over 183m.

| Model | Initial velocity (m/s) | Launch angle (degrees) | Range (m) |

|---|---|---|---|

| No drag | 60 | 15 | 183 |

Accounting for Drag

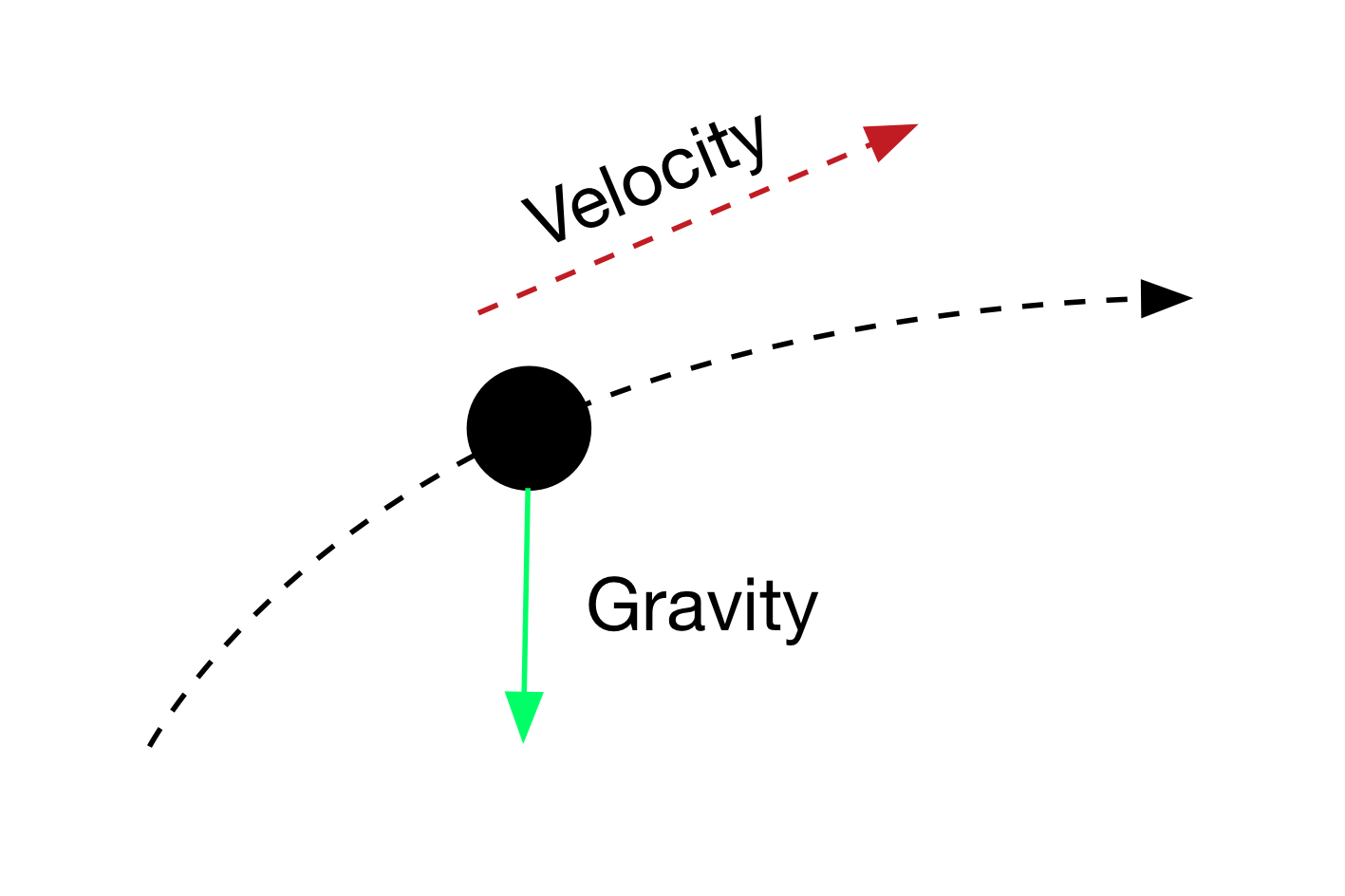

Unfortunately, games of golf are very rarely, held on the Moon. On Earth we need to account for the force of drag that air imposes on the ball. The effect drag has on the ball’s trajectory is shown in the diagram below.

Drag acts in the opposite direction to the balls velocity, causing the ball to slow down during the flight and hit the ground sooner. If we want our golf ball to fly further before hitting the ground we need to reduce this force as much as possible.

Normally, to reduce the drag acting on something, we think about making it as stream-lined as possible, like the nose of an aeroplane or front of a car. The equation below is the formula for the calculation of the force on drag \(F_D\) on and object.

Streamlining the object reduces the coefficient of drag \(C_D\) in the equation. If we were to apply this idea to a golf ball, we would conclude that the best surface should be a smooth one and measurements of this \(C_D\) at low air speeds shows that dimpled balls do initially have a higher drag coefficient.

Going by this evidence our average golfer should be able to hit a smoother ball about 10m further than a dimpled one.

| Model | Initial velocity (m/s) | Launch angle (degrees) | Coefficient of Drag \(C_D\) | Range (m) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No drag | 60 | 15 | N/A | 183 |

| Smooth ball with drag | 60 | 15 | 0.45 | 106 |

| Dimpled ball with drag | 60 | 15 | 0.60 | 95 |

However, evidence from other tests show that it is actually the dimpled ball that travels further in the real world. So what is wrong with our current model?

Turbulent and Laminar Flow

After the golf ball is hit, it has to push air out of its path, channelling it over its surface. As the air moves around the ball, the surface affects its direction of flow.

On a smooth ball, the air changes its direction without disruption in a process that is known as laminar flow. This flow change creates a wake behind the ball, shown in the diagram below.

You can see on the diagram that the ball’s motion through the air causes a zone of lower pressure behind the ball. This low pressure effectively pulls the ball back, creating drag.

On a dimpled ball, the air hitting the surface is not as smoothly deflected around the ball. This disrupts the movement of the layers of air around the ball, creating turbulent flow.

Turbulent air pockets pull in the faster moving air from further away from the ball, pulling it closer towards the surface, directing it around the sides into the ball’s wake.

In theory this air flow reduces the size of the area of low pressure behind the ball and thus should reduce the drag.

The transition between laminar and turbulent flow can be found by looking at the Reynold's number for the air. The Reynolds number is dependent on the speed the air is travelling past the ball, i.e. (from the golfer’s reference frame) the ball’s speed.

Researchers investigating golf balls have found that there is a relationship between the Reynolds number and the coefficient of drag. As the Reynolds number increases, they found that the coefficient of drag decreases until it reaches a minimum value.

This minimum value of \(C_D\) ranges between 0.1 and 0.3 depending on the shape and size of the balls dimples. If we use the average of these values in our model we find that the dimpled ball in our model now travels over 30m further than the smooth ball.

| Model | Initial velocity (m/s) | Launch angle (degrees) | Coefficient of Drag \(C_D\) | Range (m) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No drag | 60 | 15 | N/A | 183 |

| Smooth ball with drag | 60 | 15 | 0.45 | 106 |

| Dimpled ball with drag | 60 | 15 | 0.20 | 137 |

This still isn’t the full story though, as we have one more effect to consider.

Backspin and lift

When a golf ball is hit, it is given an amount of backspin. This spin introduces a new force into our model of the golf ball, lift.

As the ball rotates, the ball pulls the surrounding air with it, meaning the air flowing over the top of the ball travels faster than the air travelling under the ball. As described by the Bernoulli principle, this difference in air speed means that there is also a difference in air pressure.

The difference between the higher pressure under the ball and the lower pressure above the ball creates lift, forcing the ball upwards. This phenomenon is a by-product of the Bernoulli principle and is known as the Magnus Effect. This effect counteracts the force of gravity, allowing the ball to travel further before it hits the ground.

It has been shown in studies that the dimples on the ball’s surface are vital if a golfer wants to take advantage of this physical phenomenon to improve their game. In fact it was shown in 1949 that for smooth balls this lift was actually negative, pushing the ball down to the ground much sooner and reducing the ball’s range.

For a standard dimpled ball, the relationship between this spin and lift was found to follow the curve described by the equation where lift (L) is given in Newtons and rotational speed (N) is given in rotations per minute,

\(L=0.285 \times [1-e^{-0.00026N}]\)

By updating our physical model of the golf ball’s trajectory to take into account the new lift force, we find that the dimpled ball now travels even further.

| Model | Initial velocity (m/s) | Launch angle (degrees) | Coefficient of Drag \(C_D\) | Backspin (RPM) | Range (m) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No drag | 60 | 15 | N/A | 0 | 183 |

| Dimpled ball with drag | 60 | 15 | 0.20 | 0 | 137 |

| Dimpled ball with drag | 60 | 15 | 0.20 | 3275 | 190 |

In fact, the dimpled ball will travel further than our initial model without the effects of drag!