The Physics of Spin

Aerodynamics in Tennis

Why does topspin occur? How can one manipulate the bounce of the ball to gain a competitive advantage?

Introduction

Ever wondered how professional tennis players manage to achieve the perfect ace, lob or cross-court winner? Talent and hard work during training are definitely principal factors but the extent to which physics plays a key role in their game is often neglected.

The trajectory of a tennis ball is affected by gravitational and aerodynamic forces which act on it for the duration of its flight. Many avid tennis spectators or players will have noticed that a principle element of the athlete’s game involves the ability to apply spin to distort the ball’s path and bounce to gain a competitive advantage.

The three principal ways to hit a tennis ball are flat (no spin), with topspin or with backspin. Below we will cover the extent to which the applied spin affects the trajectory of the ball and discuss the physics behind these observations.

The physics of topspin

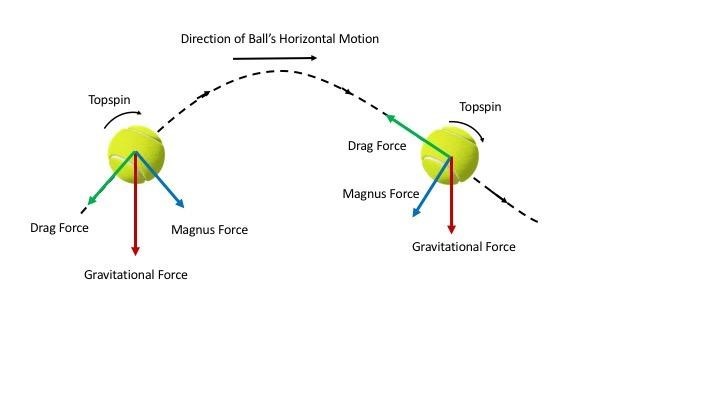

Topspin is crucial for the player as it gives them a greater consistency of play. To hit a ball with topspin, the player must exert a clockwise rotation over the top of the ball on impact. This applies a torque about the centre of the ball which causes it to spin in a clockwise direction for the rest of its path. For any ball rotating through the air about an axis perpendicular to its direction of travel, the velocity of the ball relative to the air is opposite on either side of the ball.

For topspin, the tangential velocity of the ball on the upper surface is in a direction parallel to the ball’s motion, hence the top of the ball has a larger magnitude velocity relative to the surrounding air than the rest of the ball. This then increases the drag force at this point while, by similar reasoning the drag force is reduced at the bottom surface of the ball.

This distribution of drag forces can be thought of as exerting an unequal pressure on the ball, with a greater drag force resulting in greater pressure. The resulting pressure differential then causes a resultant downward airflow force on the ball, known as the Magnus force, in the direction of decreasing pressure in accordance to Newton's third law. This additional downward force means that a player can consequently hit the ball higher and faster over the net and still have the ball land in court, thus increasing their margin of error.

As balls hit with topspin often drop from a greater height, simple equations of vertical motion will confirm that the ball will gain more velocity on its descent and consequently rebound with a greater speed in the vertical direction than a ball hit without spin. Therefore, topspin is most likely to be used to lob a player that has approached the net, or during a first serve.

Backspin

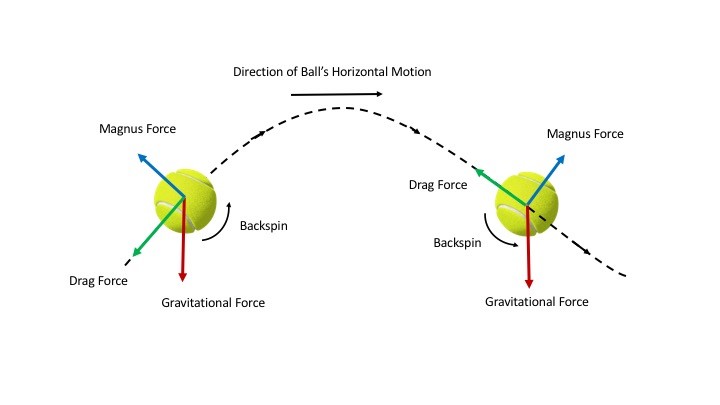

In a similar fashion, backspin is exerted on a ball when a player angles his racket back and slides it underneath the ball, giving it a counter-clockwise rotation as shown in the diagram. The key difference in this case, is that the Magnus effect now works in the opposite direction to topspin - giving the ball an upwards lift. This additional upwards force on the ball makes it appear to ‘float’ through the air.

Bounce Manipulation

As previously discussed, spin can significantly alter the trajectory of a ball, however it also has a strong influence over the subsequent bounce of the ball at the end of the receiver. To understand the motion of the ball we must separate the horizontal and vertical components of the balls velocity, as it is the ratio of the vertical velocity of the ball to its horizontal velocity that determine the subsequent angle with which the ball will rebound off the court.

To begin our analysis, we need to first calculate the coefficient of restitution (COR) of the ball on court, as this affects the vertical speed of the tennis ball after its bounce. This is found by calculating the ratio of the relative speed of the ball after rebounding off the court to its relative speed before impact. As the force of friction alters the balls spin and horizontal motion, we need to also calculate the coefficient of friction (COF) between the court and the ball. For all tennis courts, the values of (COR) and (COF) lie in the range of 0.5-1.0.

Shot variation with spin type

Flat Shot Bounce

On impact with the court a ball with no spin will initially skid, as the bottom of the ball is subject to a kinetic friction force from the court in a direction opposite to the slip velocity between the ball and the court during impact. The slip velocity is the relative horizontal speed between the point of impact between the ball and the court. This frictional force exerts a torque about the centre of the ball which gives the ball a forward rotational acceleration. The ball therefore gains topspin as it rebounds off the court surface.

As the COR of the ball is less than 1, the ball will lose vertical velocity due to the impact. In addition, as the frictional force acts in a direction opposing the horizontal velocity of the ball, this value will also be reduced.

The ratio of vertical to horizontal speed of the ball before and after the bounce is nearly the same, so the ball will leave the court at approximately the same angle as the incident ball angle. However, it will now move at a slower speed due to the smaller horizontal and vertical components.

Topspin Bounce

The forward spin of a ball hit with topspin reduces the effect of the court’s frictional force on the ball. If the tangential velocity at the top of the ball is lower or higher than the horizontal velocity of the ball, then the force of friction will act to accordingly until the two velocities are equal. For example, if the tangential velocity is greater at the upper surface of the ball than the net horizontal velocity, the force of friction will increase the ball’s forward angular velocity on impact until the two values are the same.

At this point the ball will begin to roll, and thus there is a smaller net frictional force applied to the ball compared to the flat shot example. This means that the ball loses less horizontal speed than a ball with no spin applied.

Therefore, as the vertical velocity of the topspin ball is reduced by a larger amount than its horizontal velocity, the ratio of vertical to horizontal speed is consequently lower after the bounce. This means the ball will leave the court at a lower angle than its angle of incidence. As both the vertical and horizontal components of velocity are decreased, the overall velocity of the ball will clearly be reduced.

Backspin Bounce

If the ball was initially hit with backspin, then the frictional force will, during the bounce, completely reverse the direction of the ball spin. When the ball lands on the court, the ball with then skid across the surface and the court will exert a kinetic frictional force on the ball opposing the balls horizontal motion. Due to the initial counter clockwise rotation of the ball, the force of friction acts on the ball for a longer time to make the ball rotate in a clockwise direction.

Thus, the net frictional force and reduction in horizontal speed of the ball is greater for a ball with backspin than in the previous two examples. Therefore, the ratio of vertical speed to horizontal speed is larger after the bounce than before impact. This means that the ball will leave the court with an angle greater than the angle of incidence. As before, both the horizontal and vertical components of velocity are reduced during the bounce and thus the net speed of the ball is lower after the bounce.

Interestingly, the above results are often contrary to a player’s perspective on the effect of spin on the bounce of the ball. Backspin shots are usually considered to have a lower effective bounce than topspin shots. This is because they tend to be hit lower over the net as they are subject to an upward Magnus force acting on them, unlike the downward Magnus force which acts on topspin balls. As a result, balls hit with backspin often impact the court with a lower vertical velocity than other shots, which results in an overall lower bounce.